Details:

- Aircraft Type: Supermarine Swift F4 WK272

- Date of Crash: 10th May 1955

- Pilot: Squadron Leader P.D. Thorne. (Senior RAF test pilot)

- Airfield: Boscombe Down A&AEE

- Crash Location: Paddockhurst Estate, Turners Hill, West Sussex

Report on excavation by the Wings Museum 15th June 2020.

On Saturday 15th June 2020, a team from the Wings Museum gathered at the crash site of an experimental Supermarine Swift jet aircraft that crashed at Paddockhurst Estate, Turners Hill, Sussex on 10th May 1955.

Kevin Hunt of the Wings Museum briefed those present on the dig about the procedures of the excavation and also the hazards of possible 30mm ammunition that could be buried at the crash site. This briefing also advised people on the procedures of handling significant artefacts to avoid any possible damage.

The excavation started by removing the top soil to be set aside so it could be put back at the end of the dig. Once this was safely done the JCB excavator began to carefully dig layer by layer while the recovery team kept an eye out for any telltale evidence of aircraft remains in the form of white/blue crystals in the soil. There was also a team metal detecting the spoil heap looking for smaller artefacts that might otherwise be missed.

At a depth of 2 feet the team could clearly see the remains of very corroded aluminium which, due to the acidic nature of the sandy soil, had turned into powder crystals. At this point the first of what would become a fairly common find was discovered. A turbine blade from the Avon 109 engine, badly buckled and twisted by the impact.

Finds were fairly scant and most of the finds discovered were small. As soon as any evidence of aircraft remains were discovered the area was carefully excavated by hand. By doing this a number of small artefacts were discovered including further engine turbine blades, electrical wiring, component plates and labels, shell cases from “Practice” 30mm Aden Cannon, rubber fuel tank, fragments of main wheel tyre and a section of rubber marked “inner tube”. Several airframe components were discovered with the aircraft prefix number 54 and the individual part number.

At a depth of approximately 8 feet a layer of staining was found on top of a layer of hard sandstone. This layer contained many smaller components from the engine. At this point a number of complete glass bottles were discovered along with the remains of an old shoe! The bottles included, milk bottles dated 1955, and Tizer bottles, some dated 1948 and 1952. These are evidence of the recovery team which had evidently done such a good job of the recovery of parts from the aircraft that it must have been thirsty work!

Under this layer was solid sandstone, and it was evident that any further evidence of the aircraft would not be found any deeper. Just to be sure the Ferex magnetometer was used to confirm that the excavation was void of any deep readings. The team also confirmed that the remains of the aircraft did not go off to one side of the crater and clean natural undisturbed ground signalled that this site had given up the last of its secrets. Therefore the team began back filling and making good the ground level to the satisfaction of the landowner.

Conclusions:

From the evidence of the remains of the shattered engine it would seem as though the engine hit the sandstone and was completely destroyed by the impact. The fact that the aircraft had only penetrated to a depth of 8 feet would suggest that the wreckage was largely exposed at the bottom of the crater with the larger items being removed by the RAF Recovery Team in 1955. Because of the nature of the engine failure at high altitude and the travelling speed of the aircraft we could conclude that the aircraft must have impacted the ground at a relatively shallow angle otherwise the remains of the aircraft would have penetrated a much greater depth.

The finds are now being cleaned and preserved ready for display in the museum.

The team is satisfied with its findings and a number of interesting items were found to represent this local incident in the museum to help tell the story of our aviation heritage.

museum carrying out further investigation and locating the exact crash site.

Air Commodore Peter Donald Thorne, OBE, AFC & Two Bars

(3 June 1923 – 5 April 2014) was a fighter pilot and test pilot in the Royal Air Force (RAF), who held diplomatic posts in Tehran and Moscow during the 1970s. In 1941, Thorne enlisted in the RAF for service in the Second World War, and began flight training while still only 17 years old. He was promoted to flying officer in 1943, with seniority from 3 January.

Thorne was born on 3 June 1923 in Eastbourne, East Sussex, and educated at Culford School in Bury St Edmunds.

My father Peter Thorne, who has died aged 90, was a wartime airman who became one of the leading RAF test pilots in the postwar era of British supersonic flight and aerodynamic development.

Born in Eastbourne, to Donald and Olive (nee Dyson), he attended Culford school, Suffolk; his father died of pneumonia when he was six. Enlisting straight from school in April 1941, after a short course at Edinburgh University and training in Canada, Peter was flying Typhoons in 193 Squadron (1942-43). He briefly flew Mustangs (170 Squadron) before leading a training unit in Peterborough.

Re-enlisting after the war, by 1947 he was a flight commander at RAF Leconfield, East Riding. He first met my mother, Mary (a Waaf radio operator), at her 21st birthday party and they married in 1951. He was awarded the Air Force Cross in 1947, with bars in 1951 and 1956.

In Nicosia (1948-51), he helped to train Middle East fighter squadrons. After the Empire Test Pilots’ School in 1951, he was stationed at Boscombe Down, testing second-generation jet fighters, particularly as senior test pilot on the Supermarine Swift programme: his honest assessment of the plane’s shortcomings in 1954 influenced the decision not to adopt the Swift as the RAF’s mainstream fighter.

In 1955, he became the first RAF airman to undertake a preview flight of the English Electric P1A, effortlessly climbing to 30,000ft, and becoming a member of the USAF Machbusters club in an F-100 Super Sabre at Edwards Air Force base, California.

At RAF Sylt’s Flying Wing, West Germany (1958-60), he oversaw three nations’ fighter squadrons flying round the clock. He was awarded the OBE in 1960 as a wing commander. At RAF Farnborough he was in charge of experimental flying (1965-68).

As air attache to Iran in the early 1970s he witnessed the hubristic 2,500th-anniversary celebrations of the Pahlavi dynasty. He was defence attache in Moscow during the Brezhnev era before retiring as an air commodore.Air-system consultancies followed up to 1998 for Huntings Engineering and Lockheed Martin. In his latter years, he was involved with the Duxford Aviation Society and the Imperial War Museum, where he brought his typical care and exactitude to the information desk.

Mary died in late 2013. He is survived by his children, David, Susan, Gillian and me, and seven grandchildren.

Peter Thorne obituary – The Guardian

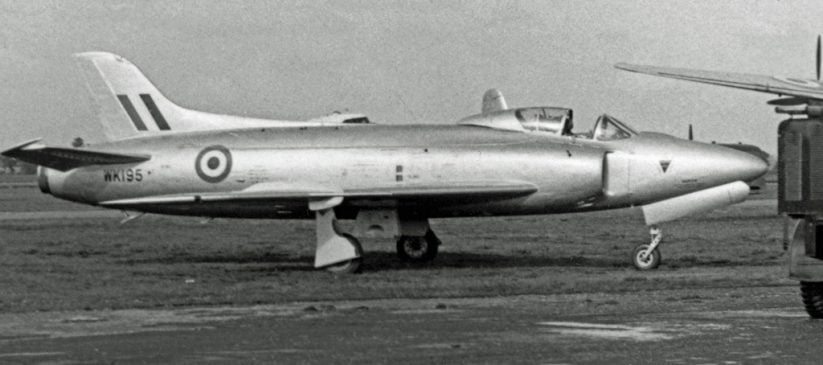

Image:

| Description | English: Supermarine Swift F.1 WK195 at Blackbushe Airport, Hants, in 1953 |

| Date | 13 September 1953 |

| Source | Own work |

| Author | RuthAS |