P9375 Crashed at Toovies Farm near Horley in Surrey.

Sgt. W.M. Krebs (NZ402194) RNZAF New Zealander bailed out, aircraft spun into the ground.

Spitfire P9375 was manufactured at Supermarine Eastleigh & completed on 1st March 1940 and began its service with the RAF on 15th March 1940 with 222 Squadron & saw extensive action during the Battle of Britain in 1940.

4th June 1941:

On 18th March 1941 P9375 was transfered to 53 OTU (Operational Training Unit). On 4th June 1941 with Sgt. W.M. Krebbs at the controls the aircraft was abandoned during an uncontrollable spin, his Spitfire crashing into a field at Toovies Farm South of Horley.

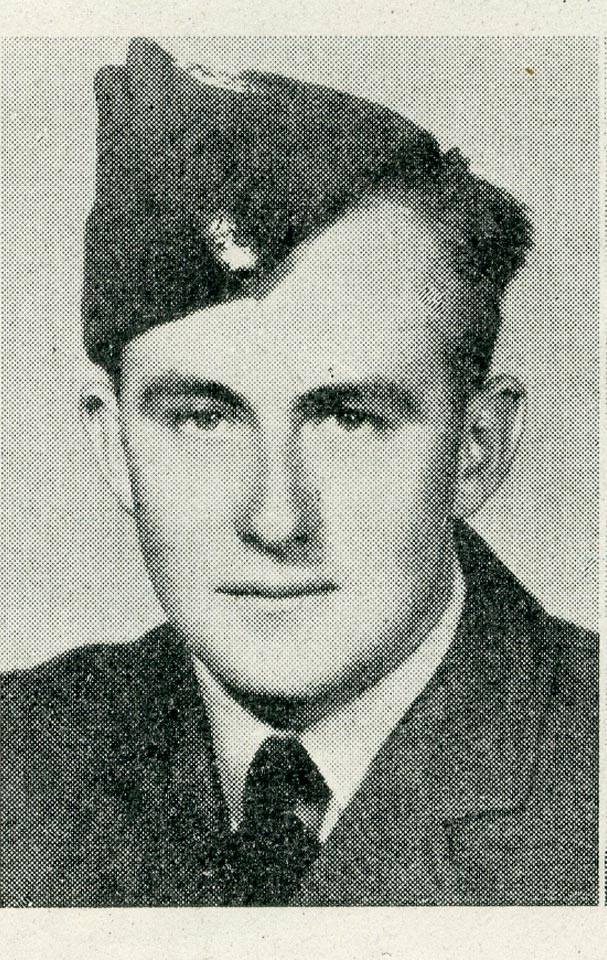

Sgt. W.M. Krebs – Luck run out:

Flt. Sgt. William Max Krebs from Gisborne New Zealand joined 485 New Zealand Squadron in August 1941, arriving from No. 609 (West Riding) Squadron which was also a Spitfire squadron. On the 26th March 1942 “Max” as he liked to be called took off that day flying a presentaion Spitfire called “Mission Bay” Serial Number W3577. The sqaudron was briefed for a mission to escort Bombers to Le Havre in Northern France. Over the target area they were engaged by enemy fighters, Max was seen to be shot down by several 109’s that made up the enemy fighter defence and while over the french coast he was seen to bail out, however both him and W3577 were lost at sea. Max’s body was never recovered and remains to this day missing in action. Max is remembered at the Runnymede Memorial, Surrey, United Kingdom. The artefacts rescued from his Spitfire that crashed at Toovies Farm by the Wings Museum will now form a display in memory of this young New Zealand pilot.

Excavation of Spitfire Mk1A P9375 23rd September 2017:

MoD Licence No. 1854.

During a previous survey of the crash site early in 2017 a magnetometer survey was conducted at the site and several small readings were recorded. Interpretation of these readings led us to believe that only small pieces remained at the crash site and we did not envisage finding anything substantial buried in the ground. Because the site would soon be consumed by new housing it was considered it worth while to carry out an excavation to recover any surviving parts from this incident that could be preserved and displayed to the public.

On Saturday 23rd of September a small team from the Wings Museum gathered at the crash site of P9375. The first task was to re-locate the exact impact point of the Spitfire which had been identified during previous visits earlier in the year. Since the field had been set aside in advance of new housing the field was now very over grown with weeds which made it harder to locate the exact point of impact.

Once the impact point was re-located we awaited the digger to arrive on site which was kindly being supplied by the land developers. We began by removing the first 12 inches of top soil over a 6 x 5 metre square which was set aside. It was possible to see from the stains in the soil where the aircraft had impacted by evidence of corroded dural aluminium which was now reduced to a white/blue crystal substance. The digger slowly scraped back layer by layer until the first finds became evident in the form of a handful of exploded .303 shell cases, a Browning machine gun mount and an ammunition feed chute. It was clear that we were digging over the remains of a wing. We continued to scrape down in this area following a circular stain in the ground until we hit natural soil. We concluded that this was were a Browning machine gun had been buried but long since recovered, no doubt by the RAF recovery crew in 1941.

The staining intersected our square excavation diagonally and we therefore moved along and followed this line until we hit a larger circular stain in the ground which was where the fuselage had impacted. The digger carefully scraped layer by layer and every 12 inches we stopped the digger and proceed to dig by hand digging out any areas of noted archaeology. Several shards of plexi from the aircraft canopy were found along with shattered remains of the wooden propeller. One of the first significant finds was discovered at a depth of 2 foot which was instantly recognised by the team to be the cockpit Flap Lever marked “up” and “down”. By excavating by hand we discovered the internal components of a cockpit instruments. As we moved along the diagonal impact area into the centre of the circular feature we began to come across the remains of 1940’s bottles, bricks, rubble, paint pots, pottery fragments and a set of iron coal tongs! Directly under this layer of back filled rubbish no doubt dating back to 1941, was a layer of burning with yet more corroded dural crystals. As we worked through the layer of rubbish we found a large circular crumpled “tear drop” panel from the Spitfire which may have been thrown in at the same time as the rubbish was deposited, perhaps the farmer made an effort to clear the site and fill in the crater.

As we excavated this area we began to find more evidence that we were in the fuselage area with remains of the TR9 radio being discovered the most significant piece being the Bakelite “Aerial Tuning” dial and control lever. We were also finding fragments of canopy Perspex and pieces of shattered front armoured windscreen glass. The spoil from this fuselage area was set aside to be searched through later utilising metal detectors. As one bucket of soil was removed from the ground our digger driver alerted us to an object dangling from the digger bucket. Aaron recovered the object for further inspection and we suddenly realised that we had found the pilots control grip brake lever twisted an distorted by the impact. With this discovery we focused our search on this spoil heap to try to locate the machine gun button that would have been located directly next to the break lever on the control yoke. Despite a careful search through the contents of the digger bucket the gun button was not located. Several of the stainless steel items such as brackets etc which had survived the fire had the prefix 300 number stamped on them, the 300 prefix part number denotes a Spitfire.

We continued to excavate the circular feature which was now beginning to reduce in width causing us to believe that the impact area had been fully excavated but to be sure we continued to dig down which revealed another small circular feature of interest. We therefore stopped the digger and proceeded to dig by hand and a brass pipe was noted to be sticking out of the ground. We carefully excavated around this and unbelievably we recovered the missing gun button. We also found the remains of the direction indicator from the cockpit instrument panel as well as the pilots cockpit ventilation control. As we neared the bottom of the impact we entered an area of blue staining and the smell of aviation fuel filled the air. This area was baron of any finds but we continued to excavate with the digger until we hit natural clay at which point it was clear that the impact area had been fully excavated. Our attention then turned to the spoil heaps where we searched with a metal detector. Many items were recovered from the spoil heaps the most significant being a complete “Venner” Time Switch – part of the Identification Friend or Foe “Pip Squeak” equipment, also a modification plate and a makers type plate from the Merlin engine.

Conclusions:

It was notable during the excavation that very little of the airframe structure was evident, it is believed that much of this was burned out and most substantial sections and pieces including the engine were removed by the recovery team in 1941.

The team excavated to a depth of 6 feet, it is likely that the majority of this wreckage was lying in a shallow open crater and was easy enough to recover at the time during the clean up operation. We are not entirely sure of the reasons why some domestic rubbish was deposited at the bottom of the crater before back filling was carried out, but perhaps it helped make up the levels or was just a convenient opportunity that could not be missed by the farmer!

We are confident that no other groups have excavated this crash site in the past. The team feel satisfied that enough interesting smaller items of interest were rescued prior to the future development of the site to make the excavation worth while. We can now form a display for the museum where these items can tell the story of a long forgotten wartime crash.

With grateful thanks to the MoD, Crawley Borough Council, Persimmon Homes Thames Valley Camberley & Taylor Wimpey South Thames Leatherhead, John Childs of Castle Hill Consultants Ltd Infrastructure.