On 28th September 1940 Pilot Officer Richard Courtney Graves was in combat over the south of England flying Hawker Hurricane Mk1 V6621 from 253 Squadron based at RAF Kenley. He was injured in combat with Bf109s over Weybridge, Surrey when his Hurricane was mistakenly attacked from behind by a 501 Squadron Hurricane and set alight.

P/O Graves baled out near Chailey, Sussex, and was admitted to Brockley Park Hospital, Haywards Heath. His Hurricane plummeted to earth and crashed near Townings Farm, Chailey and burnt out.

Fortunately P/O Graves lived to tell the tale, and in post-war years was able to tell the story to his family. He remembered seeing the Hurricane in his rearview mirror firing, shortly before being hit. He himself was very close to an Me109 at the time and, no doubt, in the confusion of battle, his Hurricane was caught in a burst of machine gun fire from the 501 Squadron machine.

This kind of “blue on blue” incident unfortunately still happens today, the reality of war in any time period has a price to pay.

Pilot – P/O Richard Courtney Graves RAFVR (83289):

Richard Courtney Graves was born on 3rd April 1921 in London. His father, Arnold Graves, was of Irish descent and his mother, Marie Antoinette Hinot, was French. His father had served in the RFC and subsequently the RAF in WW1 and had been with 30 Squadron in the Middle East.

Graves was educated in England and France, attending a Roman Catholic boarding school in France when his mother returned there together with his younger sister after her husband walked out of the matrimonial home.

He joined De Havilland as an apprentice at Hatfield in 1939, also joining the RAFVR as an Airman u/t Pilot. Called up on 1st September 1939, he completed his flying training at 9 FTS Hullavington, was commissioned and arrived at 6 OTU Sutton Bridge on 17th August 1940.

Richard Graves received his commission to the rank of Acting P/O on probation on 17th August 1940 and was later confirmed in the rank of P/O. He had been flying with 253 Squadron briefly from 9th to 13th September 1940 but was posted to 85 Squadron from 14th to 27th September 1940 before being posted back to 253 Squadron at RAF Kenley on 28th September. The very next day he was in combat over the south of England in Hurricane V6621 and injured in this combat with an Bf109 over Weybridge, when his Hurricane was mistakenly attacked by a 501 Squadron Hurricane. Earlier in the day he had himself shot down a Bf109.

Richard Graves continued service after his crash at Chailey and post war life:

Graves was flying one of twenty-four Hurricanes which flew off HMS Ark Royal to reinforce Malta on 27th April 1941. He joined 261 Squadron and went to the Middle East when the squadron was disbanded in May. He then joined 30 Squadron and served with it in Egypt, the Western Desert and later in Ceylon in 1942. Graves was released from the RAF in 1947 as a Squadron Leader.

He then held various short-term jobs with French Radio, UNESCO and others until he went to Morocco to visit his mother who had re-married a French General who, at that time, was the last Military Governor there.

He joined Mobil Oil and met his wife-to-be when posted to Casablanca. His next posting was Dakar, Senegal in 1954 as the depot manager for Mobil Oil at the airport. He remained with Mobil Oil in Aviation Sales and Marketing for the whole of ex-French West Africa until the early 1970s when he took early retirement, having moved to Paris in the early 1960s.

He moved away from the Paris area to Épinal in the east of France. While driving home one evening in July 1978 he suffered either a diabetic coma or heart attack, and tragically Mr Graves passed away.

Excavation of Hawker Hurricane V6621 by the Wings Museum

Thursday 14th September 2017. MoD Licence No. 1847

On Thursday 14th of September 2017, a team from the Wings Museum gathered at the crash site of a Battle of Britain Hawker Hurricane, Serial Number V6621. The aircraft came down at Long Ridge Farm, Chailey, Sussex on 29th September 1940.

Kevin Hunt of the Wings Museum briefed those present on the dig about the procedures of the excavation and also the hazards of possible .303 ammunition that would possibly be buried at the crash site. This briefing also advised people on the procedures of handling significant artefacts to avoid any possible damage.

We had the privillege of having the son and grandson of the pilot present on the dig to witness the recovery of the remains of their father/grandfather’s Hawker Hurricane from its resting place, where it had laid for the last 77 years.

The site of the excavation was then cordoned off with hazard tape and, after a deep scan survey with a Magnetometer, the impact site (recorded during previous deep surveys) was pegged out ready for the top soil to be removed by the excavator.

Once the first 12 inches of top soil was removed and set aside, to be reinstated once the dig was complete, we then instructed the digger driver to slowly and carefully scrape back six inches of soil at a time, allowing us to examine the soil for any evidence of the impact point.

The first evidence of the impact of the Hurricane was highlighted by an area of chalk which is not natural to the area and this is believed to be the material used to back fill the crash site in 1940 by the RAF Recovery Team.

In the middle of the chalk deposit was a darker area of natural clay soil. We understood from a book “The Battle of Britain Then and Now” that the site had been excavated in the 1970s. We believe that this area of darker clay deposit was evidence of disturbance from that excavation.

As the digger excavated and scrapped back layer by layer, the very first evidence of the aircraft could be seen in the form of “Dural” (aluminium), along with fragments of shattered wooden propeller.

We decided to focus the excavation to one side of the main impact area where the team had recorded a strong magnetometer reading. We hoped that that might have located the remains of a wing, and potentially .303 Browning Machine Gun parts.

As we removed the earth six inches at a time, one of the members of the team discovered a browning machine gun mount. Apart from this find and a few rounds of exploded .303 ammunition very little else was recorded.

Finally, at a depth of four feet, a large iron object was discovered, the digger was stopped and the team began to dig the object by hand.

Unfortunately, this item turned out to be a section of cast iron pipe with the remains of several shattered clay pipes located underneath. With this object removed the magnetometer was used to determine if any other anomalies were present. With a careful and extensive grid pattern search, the magnetometer did not record any other readings. It is possible that this was the remains of an old land drain that was perhaps damaged by the Hurricane when it crashed to earth in 1940.

With this area exhausted, the dig moved over to focus our attention on the main reading, and the digger, once again, began to scrape down six inches at a time… until the first significant remains of the aircraft were discovered at a depth of approximately three feet.

One of the first finds was a brass union from the aircraft coolant system which was in good condition.

As the team excavated by hand, the burnt remains of the tail wheel tyre, together with the axle still in position were discovered. The word “Dunlop” could be made out and this item was carefully excavated and lifted out of the soil.

The tail wheel tyre was discovered just to one side of the impact area and because the tail wheel remains retained various assemblies (such as the tyre, axle and three stainless steel bolts for the wheel hub which had long since corroded away) we believe this was evidence of an area that had been missed by the recovery carried out in the 1970s.

Having carefully extracted the tail wheel tyre, another find was discovered in the form of a steel tube from the fuselage structure, pointing vertically into the ground. This was carefully extracted and found to retain one of the Stainless Steel “Fish Plates” which was so typical of the Hurricane airframe structure.

By digging this area by hand, many other smaller components were retrieved including sections of wooden propeller, smashed engine casing, brass cowling fasteners complete with the part number, wiring and several more stainless steel fuselage brackets.

Lengths of stainless steel wire intersected the excavation area which were the tension wires from the fuselage area that kept the fuselage frame under tension during flight.

As this area was now cleared of finds, the digger was used to clear the loose soil out of the excavation area so that the team could begin digging once again by hand. One of the team members discovered an area where a number of larger items were tangled together, including a centre section about 14 inches long and some other steel structural brackets from it.

Tangled in with the remains of the fuselage tension wires were some larger engine components, including a shattered oil filter scavenge pump, cylinder head bolts, and sections of engine casing with exhaust outlets complete with an exhaust valve still present.

Other airframe brackets and twisted tubes were recovered along with a completely squashed cylinder liner. What was amazing about this find is that the piston was completely withdrawn from the liner before being squashed flat by the final impact. This would suggest that the main engine block was completely shattered from the impact. The engine artefacts showed evidence from fire damage so we can conclude that the aircraft set alight from the engine area.

Slightly to one side of the engine remains of a few internal components of cockpit instruments were found, along with a very corroded Air Speed instrument face. In this area we also recovered a complete Boost gauge instrument face, together with an oxygen gauge, both in good condition. These important finds were bagged for attention later when they could be properly cleaned and preserved.

As the team worked through the engine remains, the propeller hub was discovered at a depth of six feet and at a 35 degree angle, pointing South East. We carefully exposed the propeller hub until we could tie a lifting strop around it, allowing the mechanical excavator to carefully lift it out of the hole.

By this point the smell of 70 year old avgas filled the air.

The propeller hub was found to be in very good condition, preserved in engine oil and fuel.

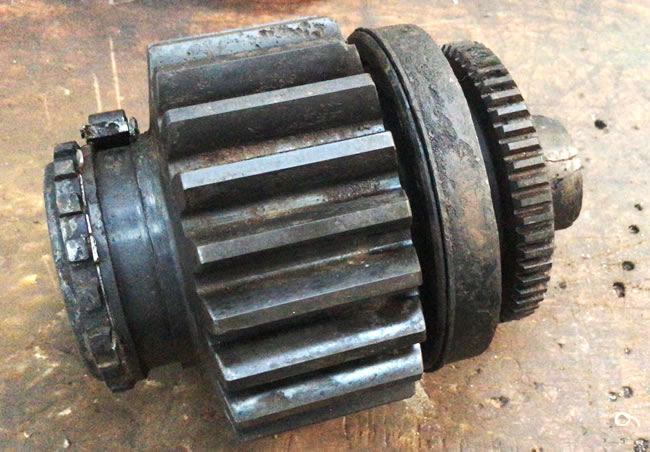

Once the hub had been removed, the team carefully excavated by hand and discovered the engine pinion gear which was very close to where the propeller hub had been recovered.

We continued to excavate by digger until we hit natural soil, but no further remains of the aircraft were discovered.

Our attention turned to the spoil heaps which were carefully searched by metal detector before being back filled into the excavation hole.

The top soil set aside earlier was then finally spread over the area of the excavation and the area was carefully levelled out by the digger to ensure the site was left in a satisfactory condition.

Conclusions:

The evidence of the remains of the shattered engine would back up reports at the time that the aircraft was on fire, forcing the pilot to bail out.

From the stainless steel airframe brackets, and part number stamps, we could tell that the aircraft was one of those constructed at the Gloster aircraft factory due to the fact that the part number had the prefix “G”.

We could also confirm that the aircraft had indeed been excavated before, most likely by hand, which would have restricted the size and extent of the excavation. The fact that the aircraft had only penetrated to a depth of six feet would suggest that the wreckage was largely exposed at the bottom of the crater with the larger items being removed by the RAF Recovery Team in 1940.

The finds are now being cleaned and preserved ready for display in the museum. The team is satisfied with its findings and a number of interesting items were found to represent this Battle of Britain incident in the museum. The experience also fulfilled the wishes of the relatives of P/O Graves who had in the past tried to locate the crash site. A presentation board is now being prepared for the family and also for the farm shop which is situated near by.

With thanks to the MoD, Landowner, Townings Farm Shop, John our digger driver, our Wings Museum volunteers and a special thank you to the Graves family.